I am all fascinated with the brain, sometimes I look at my brain as my best friend and on other days … not so much. I’ve learned about the brain in school but the course I took (neuropsychology) was more general knowledge. These days I am really interested in the topic of depression. I pair my knowledge (honestly, I need to dust off my knowledge from 15 years ago!) with research I find online. I am not a scientist though. I hope you’ll enjoy my findings and don’t hesitate to leave your comments below!

What do we think, know and how we medicate the brain with depression.

Popular lore has it that emotions reside in the heart. Of course, all things beautiful are in the heart, love, joy, peace … Science, though, tracks the seat of your emotions to the brain that regulates mood. Researchers believe that — more important than levels of specific brain chemicals — nerve cell connections, nerve cell growth, and the functioning of nerve circuits have a major impact on depression. Still, the understanding of the neurological setup of mood is incomplete.

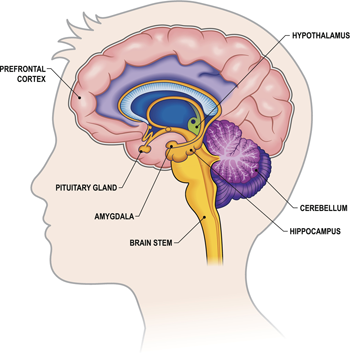

Areas that play a significant role in depression are the amygdala, the thalamus, and the hippocampus[1]. Imagine the general function of those regions being influenced by depression or vice versa.

The amygdala is part of the limbic system, that is associated with emotions such as anger, pleasure, sorrow, fear, and sexual arousal. The amygdala is activated when a person recalls emotionally charged memories, such as a frightening situation. Activity in the amygdala is higher when a person is sad or clinically depressed. This increased activity continues even after recovery from depression.

The thalamus receives most sensory information and passes it on to the cerebral cortex, which directs speech, behavioral reactions, movement, thinking, and learning. Some research supports the link of sensory input to pleasant and unpleasant feelings.

The hippocampus is part of the limbic system and has a central role in processing long-term memory and recollection. Interplay between the hippocampus and the amygdala may be illustrated as “once bitten, twice shy.” It is this part of the brain that registers fear when you are confronted by a barking, aggressive dog, and the memory of such an experience may make you afraid of dogs later on. This will be important later on, when I’ll discus the effect of depression on memory and how those two interact.

Research shows that the hippocampus may be smaller in people who experienced depression. The more bouts of depression, the smaller the hippocampus. Stress, which plays a role in depression, may be a key factor here, since experts believe stress can suppress the production of new neurons (nerve cells) in the hippocampus.

Research suggests that ongoing exposure to stress hormones impairs the growth of nerve cells in the hippocampus.

What does this have to do with medication?

Researchers are exploring possible links between sluggish production of new neurons in the hippocampus and low moods. The answer may be that mood only improves as nerves grow and form new connections, a process that takes weeks. In fact, animal studies have shown that antidepressants do spur the growth and enhanced branching of nerve cells in the hippocampus.

So, the theory holds, the real value of these medications may be in generating new neurons (a process called neurogenesis), strengthening nerve cell connections, and improving the exchange of information between nerve circuits. If that’s the case, depression medications could be developed that specifically promote neurogenesis, with the hope that patients would see quicker results than with current treatments.

What about the dopamine and serotonin? And genes? Aren’t there genes involved in the process? All of those will be covered in this small, pleasant series. If you’re a curious person and you want to know more about depression and the brain, you’re very welcome to keep reading and discovering with me.

References:

[1] https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression

Picture 1 click here

Picture 2 click here

I’m really looking forward to reading these entries. The further I get into recovery the more I want to understand what used to happen in my brain and what is happening now.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Same here, I am really curious how it all works – at least to the extend that we know and that I can understand. Glad you like the series 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

The series will be on Tuesdays, so on a weekly basis. More or less, depends on my ‘brain’. But not daily, just that you know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The benefits from ketamine really support this idea, since it promotes release of BDNF and synaptogenesis.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As far as I know the brain is just an organ that helps us drive to the pharmacy to get our meds, the mind is what needs to be observed. And the mind that we think of as our mind is said to be our ego, not in the Freudian way. And the ego is said to be a collection of behavior patters, memories and fears, and is unilaterally not real.

Now my brain and my mind hurt… 😮

LikeLiked by 3 people

I meant ultimately not real. My mind is good at grammar but my brain needs stronger glasses.

LikeLiked by 3 people

So cute, a brain with glasses 🙂 See your brain needs support too 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

Aha! Interesting things in my comments 🙂 Not in a Freudian way, good you specified. Still all not real but research shows that when meditating the brain itself changes patterns. So I do believe it is real.

The suffering for me is real and when my brain gets some support, my mind can be observed, instead of shattered.

I haven’t written about it (yet) but in the worst and the beginning of my illness I couldn’t speak. The words didn’t connect to my brain so driving to the pharmacy was out of the question. But it is possible – in my case – that the mind carved some pathways into my brain. I do believe that is possible. It is a whole discussion! 🙂 Please don’t hurt your brain over it and relax the mind 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’ve been trying to relax my mind since I was very young Kacha and it said: Hell no-go-go-go. Fortunately I no longer use drugs and alcohol because that didn’t work either. I have learned that to fight myself is ridiculous (not that I don’t still do it). 😦

LikeLiked by 4 people

Life is such a journey!

LikeLiked by 2 people

An interesting follow-on question would be what causes what. Does depression cause changes in the brain or vice versa? I suppose that is unknown.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The latest research shows that the size of specific brain regions can decrease in people who experience depression. It’s also true, in some case, that changes in brain structure i.e. brain damage can cause depression. But I’ll leave Kacha to explain in her own lovely inimitable way.

I’m loving the series Kacha 🙂 Neuropsychology was way above my pay grade 😉

LikeLiked by 3 people

Oh I have a lovely inimitable way 🥳 Thank you for such a nice compliment!

The brain in itself can change, an example would be dementia (which can be the result of a predisposition). The symptoms of early dementia can be confused with depression in elderly people. The good news is that the brain can recover from different things, its plasticity is unbelievable. With support of therapy and medication adaptations are possible. But why some people are struggling with addiction and others with depression or more anger issues or just nothing we don’t really know. It is an ongoing question in developmental psychology; what is ‘nurture’ and what ‘nature’? Mostly we see the effect of both in one person.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hey, you’re welcome 🙂 Gosh, for such a small organ, the brain is ‘huge’ and is responsible for so much. Dementia is a good example and much as I loved working with the elderly, I really struggled ith dementia, I found it so draining and was always exhausted at the end of each shift. I take my hat off to all the nurses/staff and families who care for people with dementia.

Nature/nurture is another biggie – I was going to do a post on that soon. Would I be stepping on your toes? Caz x

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ow you’re so very sweet, of course not, no toes to be seen here 🙂 Write what you want to write, I love to read it!

My grandmother had dementia, it runs in the family, hmm… It was very hard to deal with, for her but also for us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That must have been awful for your grandmother and for you. I feel for you Kacha 🙂 x

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is such a good question which we know partly some anwsers to. Mostly the consensus could be that there is some kind of vulnerability which comes into play when triggered by life circumstances. That is not always the case. I’ll write about the role of genes in one of the following Tuesdays.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting that the hippocampus shrinks in depression while activity in the amygdala increases. From what I’ve heard of depression and my own brushes with it, I would have expected lower activity in the amygdala. The warning signs I always watch for are a dulling of feeling and reaction, both for positive and negative emotions. Perhaps that’s just the way my particular brain works. Since my amygdala seems overly active most of the time, I really notice a sudden lack of that reactivity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your interesting remark here 🙂 As I understand the connection between the amygdala activity and depression: the activity arises, this increases a tension, you can feel more anxious, more ‘on the edge’, more sensitive like you had a good ‘scare’ but that feeling doesn’t restore itself to normal, it keeps being more ‘high’. When feeling anxious or more tense, this can wear you out to the point other feelings become dull. Feelings like pleasure or even your motivation to do something. The one takes too much and doesn’t leave enough for the other. I hope I could clear this up. I must also say that that is how I understand it, I can be wrong here and there as the matter is not that simple.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I see! That makes sense. I have experienced the constantly-on-edge feeling. Perhaps my experience of lowered anxiety being a danger sign is from that state leading to an eventual exhaustion. Ah, brains. So weird yet so important!😉

LikeLiked by 1 person